I’ve got a confession to make. For years, I’ve been that insufferable person at dinner parties who asks where the vegetables were grown while everyone else is just trying to enjoy their food. My friends have developed a special eye roll reserved exclusively for when I start banging on about food miles or seasonal eating. My mum still tells the story about the time I refused to eat imported strawberries at Christmas when I was nine, dramatically pushing the plate away and announcing, “These shouldn’t exist right now!” God, I was an intense child.

But here’s the thing—despite being a complete pain about it, I wasn’t entirely wrong. Just… lacking in social graces. And possibly some perspective. Because bioregional living isn’t actually about perfection or purity. It’s about developing a relationship with the place you actually inhabit, rather than living as though you could be absolutely anywhere on the planet.

I learned this properly about seven years ago when my car broke down in the middle of nowhere during a research trip in Devon. I ended up stuck in a tiny village for three days while waiting for parts to arrive. With nothing better to do, I wandered into the local pub and got chatting with an older bloke named Jim who, it turned out, had never lived more than five miles from where he was born. Initially, I was fascinated in that slightly condescending urban-person way—how quaint! But after several hours of conversation (and yes, several pints), I realized that Jim knew more about the actual functioning ecosystem around him than I did with all my environmental science credentials.

He could tell you exactly when different fish would be running in the local stream, which wildflowers appeared in which order each spring, where the best mushrooms grew after autumn rains, and a dozen uses for plants I’d have walked past without noticing. He didn’t call it “bioregional living”—he would’ve laughed himself silly at that term—but that’s exactly what it was. His entire existence was calibrated to the natural patterns and offerings of his immediate environment.

I went home to Bristol feeling like a fraud. There I was, sustainability editor, literally writing articles about ecological living while having no bloody clue what was actually happening in the ecosystem outside my flat. I couldn’t have told you what trees lined my street, let alone when they flowered or fruited. I was buying organic veg from halfway across the country while ignoring the seasonal abundance that existed right where I lived.

So I decided to try an experiment in place-based living. For one year, I would attempt to source at least 50% of my food from within a 50-mile radius of my home. I’d learn the seasonal patterns of my region, understand its natural resources, and generally try to stop living as though I existed in some placeless void where everything is available all the time.

The first month was a nightmare. I realized how incredibly dependent I was on the global food system. My normal cooking suddenly felt impossible. No lemons? In WINTER? But how would I make… literally anything? I’d stand in my kitchen having minor existential crises over salad dressing. My flatmates thought I’d gone properly around the bend when they found me frantically researching “medieval vinegar substitutes” at 2 AM. They weren’t entirely wrong.

But gradually, something shifted. I started visiting farmer’s markets and actually talking to the people growing my food. I joined a local veg box scheme and had to learn to cook whatever weird root vegetables showed up each week. (Side note: if anyone needs seventeen different recipes for swede, I’m your girl.) I even started foraging—cautiously at first, armed with three different plant identification apps and the constant fear I was about to poison myself with deadly nightshade.

The whole process forced me to pay attention to my actual environment in a way I never had before. I started noticing patterns—when the elderflowers bloomed along the cycle path, where blackberries appeared in late summer, which parkland trees dropped edible nuts in autumn. My walks became food reconnaissance missions. I’d come home with pockets full of wild garlic in spring and crab apples in fall.

This regional approach to sustainability opened my eyes to how disconnected most of us have become from local ecological systems. Community gardens started making perfect sense as places where bioregional living principles could be practiced collectively, sharing knowledge about what grows well in specific microclimates and soil conditions.

Now, I’m not going to pretend I transformed into some self-sufficient woodland sprite. Let’s be real—I still bought coffee and chocolate and spices and a million other things that don’t grow anywhere near Bristol. I had failures and cheats and moments of weakness involving out-of-season avocados. But something fundamental had changed in my relationship with place.

I started understanding the rhythm of the Southwest English growing season not as an abstract concept but as something that directly affected what ended up on my plate. I knew when the first local asparagus would appear (and then consumed it in such quantities that my wee smelled funny for two solid months). I celebrated the brief, glorious British strawberry season instead of eating mediocre imported ones year-round. Food started to have a context, a season, a connection to weather patterns I was actually experiencing.

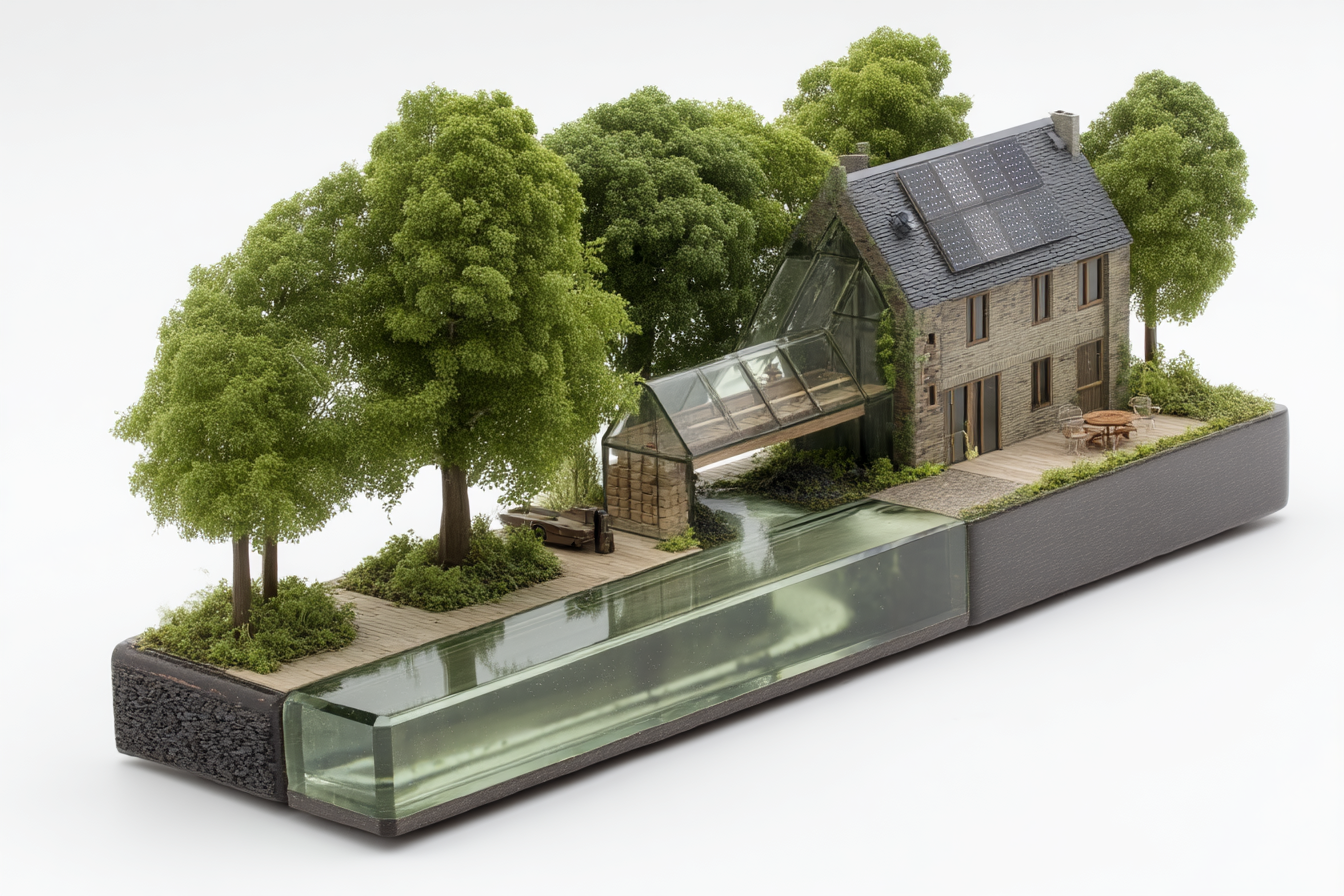

And it went beyond food. I became fascinated with traditional building methods that used local materials—cob houses in Devon, limestone in the Cotswolds, brick in the city. I started noticing how older buildings were oriented to maximize natural light and heat in our particular climate, while newer developments often ignored these place-specific considerations entirely. I developed a slightly obsessive interest in vernacular architecture that culminated in me dragging dates to look at “interesting rooflines” rather than going to normal places like restaurants or cinemas. Amazingly, I’m still single.

The thing is, bioregional living isn’t some new, trendy concept. It’s actually the oldest way of living there is. For most of human history, people had no choice but to align their lives with local ecological systems because there wasn’t a global supply chain bringing mangoes to England in December. They built with materials they could source nearby, ate what grew in their climate zone, and developed cultural practices that reflected the specific characteristics of their home places.

What we’re calling “bioregional living” now is really just remembering something we’ve forgotten—that we don’t exist in some abstract nowhere, but in specific somewheres with specific characteristics that shape what makes sense to do there. It’s about understanding your local ecosystem, your watershed, your soil conditions, your climate patterns, and making choices that work with rather than against these natural systems.

Take water use, for instance. It makes perfect sense for someone living in Arizona to be fanatical about water conservation, to landscape with cacti and other drought-resistant plants, to capture every drop of rainwater that falls. But those exact same practices transported to Wales, where it rains approximately 362 days a year (only a slight exaggeration), would be… weird. Not wrong, exactly, but disconnected from the actual ecological reality of the place.

This is what frustrates me about one-size-fits-all sustainability advice. Those “10 Ways to Go Green” articles that could be written about anywhere, for anyone, miss the entire point of ecological thinking, which is that different contexts require different responses. The practices that make sense in a dense urban environment are different from those that make sense in a rural setting. What works in a cold climate might be pointless or even counterproductive in a tropical one.

Understanding local ecology means recognizing these context-specific needs. Sustainable agriculture practices vary dramatically depending on soil types, rainfall patterns, growing seasons, and native ecosystems. What works brilliantly in one bioregion might be completely inappropriate in another.

About four years ago, I was invited to speak at a sustainability conference in California. I was excited to see some of the solar installations and water conservation systems I’d read so much about. But I also experienced a moment of genuine confusion when I saw homes with lush green lawns in the middle of what was essentially a desert. Coming from England, where keeping grass green is rarely the problem (getting it to stop growing long enough to mow is the actual challenge), the cognitive dissonance was striking.

These weren’t “bad” people—many had solar panels and electric cars and all the other trappings of environmental consciousness—but they were living in a way fundamentally misaligned with their actual bioregion. It highlighted how our modern lifestyle often operates in complete disconnection from local environmental conditions.

And look, I get it. We all do this to some extent. Our entire modern lifestyle is built on the premise that we can overcome local limitations through technology and trade. And there are genuine benefits to that—I’m not suggesting we go back to some pre-industrial existence where you die if your local crop fails. I like antibiotics and the internet too much for that kind of radical localism.

But I do think there’s a middle path, where we maintain the benefits of global connection while redeveloping a deeper relationship with our actual localities. Where we don’t completely abandon global trade but recognize that perhaps eating tropical fruits in northern Europe all year round isn’t the most sensible approach. Where we design our homes and communities in ways that work with, rather than against, the specific conditions of the places we inhabit.

For me, that’s meant a gradual shift toward more regionally appropriate living. I still use the global supply chain—I’m not making my own shoes from locally sourced leather or anything properly hardcore. But I try to pay attention to what makes ecological sense where I actually am. I’ve learned which native plants support local pollinators in my small urban garden. I’ve switched to a green energy supplier that sources power from regional renewable installations.

Most importantly, I’ve stopped seeing my environment as a neutral backdrop against which I live my life, and started recognizing it as a complex, specific system that I’m embedded within. The watershed I’m part of, the soil under my feet, the climate patterns that shape my region—these aren’t abstract concepts but concrete realities that logically should influence how I live.

Bioregional principles extend beyond just food and materials to energy systems too. Renewable energy sources make different amounts of sense depending on your local conditions. Solar power is brilliant in sunny climates but less effective in cloudy northern regions where wind or hydro might be better options.

I’ve become a bore about traditional preservation techniques for dealing with seasonal gluts of produce. Fermentation, dehydration, root cellaring—these aren’t just trendy homesteading hobbies, they’re technologies developed specifically for extending the availability of local seasonal foods. My kitchen now has more fermenting jars than a proper adult should reasonably own.

The social aspects of bioregional living have been just as important as the practical ones. Getting to know local farmers, foragers, and food producers has created a sense of community connection I didn’t even realize I was missing. There’s something profound about knowing the people who grow your food, understanding the challenges they face with weather and pests and market pressures.

The importance of buying local becomes visceral when you’ve met the person who grows your vegetables and understand the ecological and economic systems that support their work. It’s not just about reducing transportation emissions—though that matters—it’s about being part of a local food system that supports both ecological and social resilience.

This approach doesn’t have to be all-consuming or perfect. My own version certainly isn’t. Just yesterday I bought bananas, which definitely don’t grow within 500 miles of Bristol, let alone 50. I’m writing this on a laptop made from materials sourced from across the globe. But each step toward bioregional alignment feels like developing a more honest and functional relationship with the actual place I inhabit.

The built environment offers another avenue for place-based living. Creating a sustainable outdoor space means understanding what naturally wants to grow in your specific soil and climate conditions, rather than forcing inappropriate species to survive through constant inputs of water, fertilizer, and pesticides.

I’ve learned to see my small urban garden as a microcosm of the larger bioregion. The plants I choose, the way I manage water and soil, even the materials I use for paths and structures—all of these can either work with local ecological patterns or fight against them. Native plants that support local insects and birds make more sense than exotic specimens that offer nothing to the local ecosystem.

Weather patterns have become something I pay attention to rather than just endure. Understanding seasonal rainfall distribution helps with planning garden activities and water management. Knowing typical frost dates and growing season length informs food production decisions. Even indoor comfort becomes more achievable when you work with rather than against local climate patterns.

And honestly? Food tastes better when it’s grown in proper soil nearby and eaten in season. Buildings are more comfortable when they’re designed for the actual climate they exist in. Life makes more sense when it’s connected to the ecological realities that ultimately govern everything, no matter how much we pretend otherwise.

So maybe start by just noticing where you are. What actually grows there naturally? When are things in season? What were buildings traditionally made from before global supply chains? What’s the rainfall pattern, the soil type, the native ecosystem? You don’t have to revamp your entire existence overnight. Just begin paying attention to place.

The rest tends to follow naturally—rather like ecology itself. Once you start seeing your local environment as a living system rather than just scenery, it becomes obvious which choices align with ecological realities and which fight against them. Bioregional living isn’t about returning to some romanticized past—it’s about moving forward with the wisdom to recognize that we’re not separate from the natural systems that sustain us, no matter how much our modern lifestyle encourages us to forget that fundamental truth.