I had a proper lightbulb moment about ecosystem services during a particularly miserable camping trip in Wales. It was supposed to be a romantic weekend with my then-boyfriend, but after two days of relentless rain, we abandoned our soggy tent and sought refuge in a local pub. As we nursed our pints, an elderly farmer at the next table struck up a conversation. He’d been watching the hillsides getting progressively barer for decades as ancient woodland was cleared for more grazing land.

“Used to be you’d never get flooding down in the village,” he told us, gesturing vaguely toward the window where rain continued to lash against the glass. “Those trees up there did more than look pretty. They held the water back, like a sponge.” He wasn’t using fancy terminology, but he was describing ecosystem services as clearly as any ecological textbook I’d ever read.

The boyfriend didn’t last (turns out I’m not great company when cold, wet, and analyzing soil erosion patterns), but that farmer’s observation stuck with me. He understood intuitively what scientists have been quantifying for years – that functioning ecosystems provide services that directly support human life and wellbeing. It’s not just about saving nature because it’s beautiful or because we feel morally obligated. It’s about recognizing that our economic systems, our health, and our very survival depend on these ecological processes continuing uninterrupted.

I’m constantly amazed by how many people still think of conservation as some kind of luxury concern – something we can address once we’ve sorted out “real” economic problems. God, if I had a pound for every time someone’s told me that environmental protection is something only wealthy countries can afford to worry about! The reality is exactly the opposite. The poorer a community is, the more directly dependent they usually are on functioning ecosystem services, from clean water to fertile soil to natural flood protection.

The term “ecosystem services” itself can sound a bit cold and transactional, I know. I remember bristling at it during my university days – the notion of reducing the wonder of nature to its utility for humans felt somehow wrong. But then a professor challenged me: “If we don’t articulate the value of these services in terms people understand, how will we ever convince anyone to protect them?” She had a point. We’re hardwired to protect what we value, and we tend to value what we can measure – especially in economics and policy.

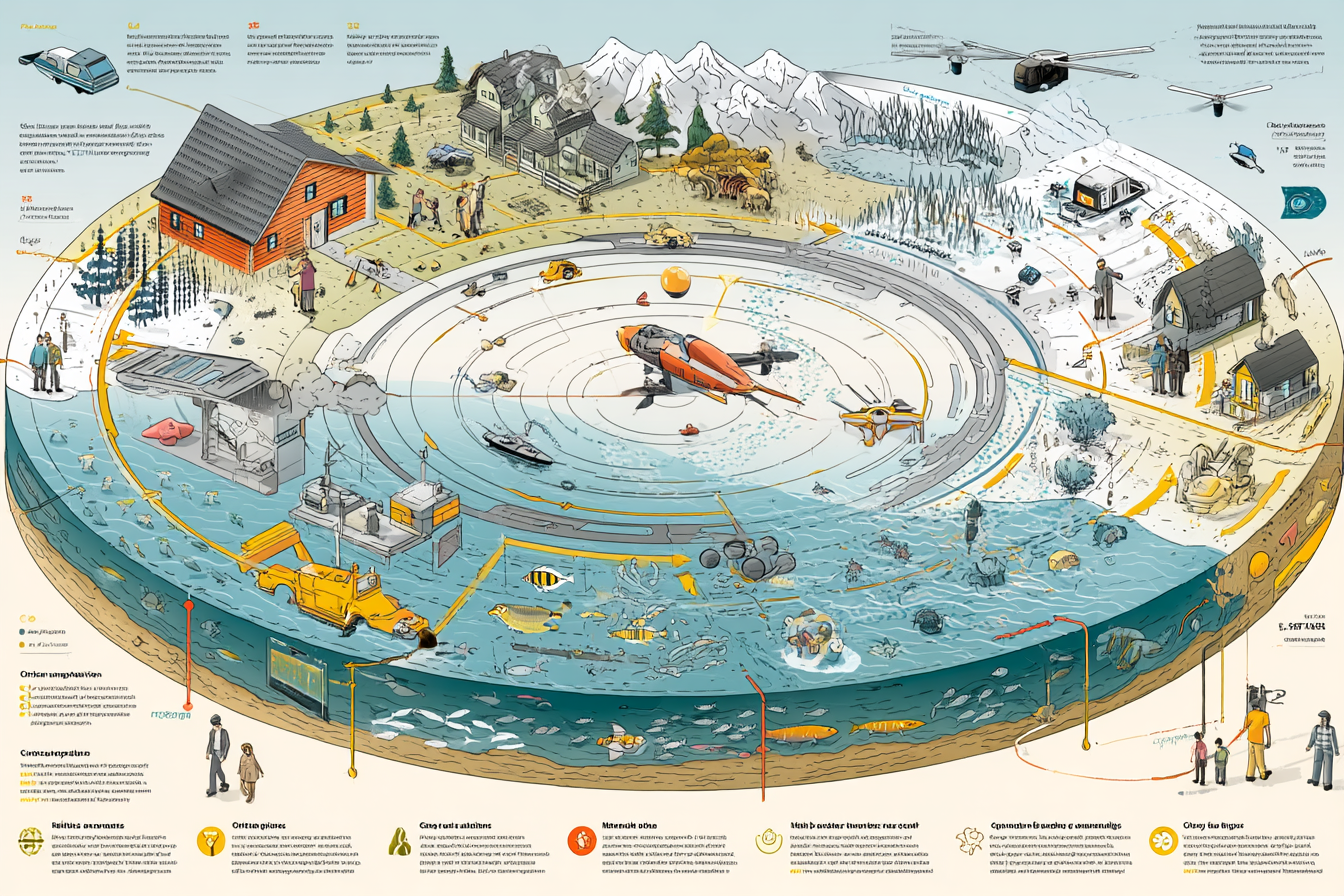

So what exactly are these services? They’re essentially the benefits that humans receive from natural systems functioning properly. Think of them as nature’s infrastructure – just as we build roads and power plants to support our lives, nature has evolved systems that provide essential services we rarely think about until they stop working.

I saw this first-hand after helping with a wetland restoration project outside Bristol. The area had been drained decades ago for agricultural land, but after repeated flooding issues, the decision was made to return it to its natural state. The neighboring farm had been spending a fortune on flood damage almost every year. After just three years of wetland restoration, the flooding had reduced dramatically – the natural water storage capacity of the wetland was doing what it had evolved to do for thousands of years before humans intervened.

The farmer, initially skeptical about “rewilding” (a term he pronounced with the same enthusiasm one might say “tax audit”), became one of the project’s biggest advocates. “Never thought I’d say this,” he told me as we stood looking over the newly established reed beds, “but this swamp is saving me more money than any infrastructure the council ever built.” I resisted the urge to correct his terminology from “swamp” to “wetland” – he was getting the important bit right.

Water regulation is just one ecosystem service. There’s also air purification (I always think of trees as nature’s air filters, quietly removing pollutants while we go about our business), pollination (without which our food systems would collapse), soil formation (which happens on a timescale of centuries, not seasons), carbon sequestration (increasingly critical as we face climate change), and dozens more. We rely on these services every single day, usually without giving them a second thought – until they stop working.

Part of the problem is that many ecosystem services don’t show up in traditional economic measurements. Nobody sends you a bill for the air purification provided by urban trees or the mental health benefits of green spaces. My friend Jun, who works in economic policy, calls these “invisible subsidies” – benefits we receive without acknowledging their source or calculating their worth. When I pressed him on how we might better account for these values, he laughed and said, “Imagine if we had to pay for the work bees do. We’d all be bankrupt overnight.”

He’s not wrong. A few years ago, I interviewed a commercial beekeeper who was renting his hives to orchards for pollination. The going rate was about £50 per hive per season, but both of us acknowledged this was absurdly low compared to the actual value of the service. One study estimated the economic value of pollination services worldwide at over £500 billion annually. Try replicating that with human labor and technology!

I’ve found that one of the most powerful ways to help people understand ecosystem services is through what I call the “replacement cost” question. That is, if this natural system stopped functioning, how much would it cost us to replace it with technology? Take water purification, for example. New York City famously invested in protecting its watershed rather than building new filtration plants – saving billions of dollars in the process. When faced with the choice between a $10 billion filtration plant or $1.5 billion in watershed protection, the economic decision became obvious even to the most hardened fiscal conservatives.

On a personal scale, my neighbor Prisha recently installed a rainwater harvesting system in her garden – partly inspired (she claims) by my incessant talk about water cycles. She was shocked by how quickly it reduced her water bills during our increasingly dry summers. “I thought you were just being your usual eco-warrior self,” she told me over our shared garden fence, “but turns out there’s actual money to be saved here.” I refrained from saying “I told you so” – barely.

The challenge we face is that many ecosystem services are what economists call “public goods” – their benefits are available to everyone, which paradoxically makes them vulnerable to neglect or exploitation. No individual owner has sufficient incentive to maintain them, even though collectively we all depend on them. It’s the classic tragedy of the commons, playing out across our landscapes.

This is why policy interventions are so crucial. Left purely to market forces, ecosystem services will almost always be undervalued and degraded. I’ve seen promising approaches through payment for ecosystem services (PES) schemes, where landowners receive compensation for managing their land in ways that ensure these services continue. A farmer upstream who maintains woodland that prevents flooding for communities downstream might receive payments reflecting the value of that flood protection service.

The UK’s Environmental Land Management scheme is attempting something along these lines, though not without teething problems. I visited a farm in Devon last year that was transitioning to this approach, moving from intensive production toward management that emphasized carbon storage, water quality, and biodiversity. The farmer was candid about the challenges: “The paperwork is a nightmare, and sometimes the payments don’t reflect the actual work involved.” But she also saw the long-term benefits: “My soil’s improving year on year, and I’m not spending a fortune on fertilizers anymore. My dad would call it getting paid to farm properly.”

Of course, economic valuation has its limits. Some ecosystem functions resist easy quantification – how do you put a price tag on the cultural or spiritual value of natural places? My grandmother used to take me blackberry picking along hedgerows in Somerset, teaching me which berries were ready and which needed more time. The joy of those afternoons isn’t something you can monetize, yet it’s part of what connects many of us to natural cycles and systems.

And honestly, there’s something that makes me deeply uncomfortable about reducing nature to a service provider for humans. It feels reductive, as if we’re saying the natural world only matters to the extent it’s useful to us. I struggle with this philosophical tension constantly – recognizing the strategic value of economic arguments while also believing nature has intrinsic worth beyond any service it provides.

But I’ve come to see it as both/and rather than either/or. We can value ecosystem services for practical reasons while also appreciating the wonder and complexity of nature for its own sake. The two aren’t mutually exclusive. In fact, they reinforce each other – the more we understand how intricately our wellbeing is tied to functioning ecosystems, the deeper our appreciation for the natural world becomes.

So what can individuals do to support ecosystem services? Loads, actually. In your garden (if you’re lucky enough to have one), you can create habitat for pollinators, improve soil health through composting, install rain gardens that help with water regulation, and plant trees that sequester carbon and clean the air. On my tiny Bristol balcony, I’ve managed to create a mini ecosystem that supports at least seven species of bees and countless other insects. My upstairs neighbor thinks I’m slightly mad, watching bees with the intensity other people reserve for sports matches, but he’s also started asking for plant recommendations for his own space.

You can also support policies and organizations working to protect and restore natural systems. This takes many forms – from voting for politicians who prioritize environmental protection to choosing products from companies committed to sustainable practices. And yes, I know how fraught those choices can be – I still remember my three-hour deep dive researching which toilet paper had the least environmental impact. (My housemates staged an intervention when they found me making spreadsheets comparing bamboo versus recycled options.)

The ecosystem services framework helps us see that protecting nature isn’t charity – it’s infrastructure investment. It’s recognizing that a healthy mangrove forest might be more effective flood protection than an expensive sea wall, that intact watersheds provide better water security than treatment plants alone, that urban green spaces improve public health and reduce healthcare costs.

That Welsh farmer in the pub understood this relationship intuitively, through direct observation over decades. Sometimes I think our challenge isn’t so much teaching people something new as reminding them of something they once knew – that our lives are inextricably linked with the ecological systems around us, and that our prosperity depends on their continued functioning. It’s not tree-hugging sentimentality; it’s practical recognition of the foundation our economies and societies are built upon. Though between you and me, I’m not opposed to hugging the occasional tree as well – for both practical and sentimental reasons.