I still remember the exact moment I fell in love with forest gardening. It was seven years ago, during a visit to Martin Crawford’s legendary forest garden in Devon. I’d read about the concept, of course—the idea of creating food-producing ecosystems modeled on woodland structures—but reading about it and experiencing it are entirely different things.

I was expecting something that looked like a slightly wild orchard, maybe with some herbs scattered underneath. What I encountered instead was this astonishingly vibrant, multilayered wonderland where every inch seemed to be alive with purpose. Towering nut trees created a dappled canopy. Fruit trees formed a productive middle layer. Beneath them grew currant bushes, perennial vegetables, herbs, and groundcovers, all intermingling in what looked to my untrained eye like beautiful chaos.

Martin was leading the tour, pointing out edible and medicinal plants I’d never even heard of, explaining relationships between species, showing how the system largely maintained itself. And there was one moment—standing in a small clearing, surrounded by abundance, listening to the insect hum and bird chatter—when something just clicked. This wasn’t gardening as I understood it. This was something vastly more profound: creating functioning ecosystems that worked with nature rather than constantly fighting against it.

I left that day with my head spinning and a car boot filled with hastily purchased unusual plants that I had absolutely nowhere to put in my tiny Bristol garden. (My housemate Theo was thrilled, as you can imagine, when I arrived home with seven different varieties of unusual mint and a Jerusalem artichoke that would eventually attempt to colonize our entire garden. Sorry about that, Theo.)

The core concept that makes forest gardening so revolutionary is ecological succession—the process by which natural landscapes evolve over time. In conventional agriculture and gardening, we typically hold landscapes in what ecologists call the “early succession” stage—think open fields, annual plants, and constant disturbance through tilling and weeding. We pour enormous amounts of energy (both human and fossil fuel) into preventing these systems from doing what they naturally want to do: grow into more complex, wooded ecosystems.

Forest gardening flips this approach on its head. Instead of fighting succession, it works with it, designing food-producing systems modeled on mid to late-succession woodland ecosystems. The goal isn’t to create an actual forest (despite the name) but rather to mimic the structure, relationships, and self-maintaining aspects of natural woodlands while filling the system with species that provide yields for humans.

The beauty of this approach became even more apparent when I visited that same forest garden three years later. While conventional gardens require the same intensive input year after year, Martin’s creation had matured and actually needed less intervention as time passed. The system was largely self-fertilizing through leaf fall and nitrogen-fixing plants. It managed its own pest problems through biodiversity. It built soil rather than depleting it. And perhaps most importantly from a practical standpoint, it continued producing abundant food and other yields with minimal ongoing labor.

I was hooked. Unfortunately, I was also living in a rental property with limited garden access. So I did what any reasonable person would do—I joined the committee of our local community garden and gradually inflicted my forest garden obsession on an unsuspecting community project. (In my defense, they’re now extremely proud of their “edible forest” area, which has become the most popular feature during open days.)

The principles I learned from that initial visit—and from years of subsequent reading, volunteering, and experimenting—have shaped not just my approach to growing food but my entire understanding of how humans can work with natural systems rather than against them. So let me share the core principles that make forest gardening such a revolutionary approach to food production.

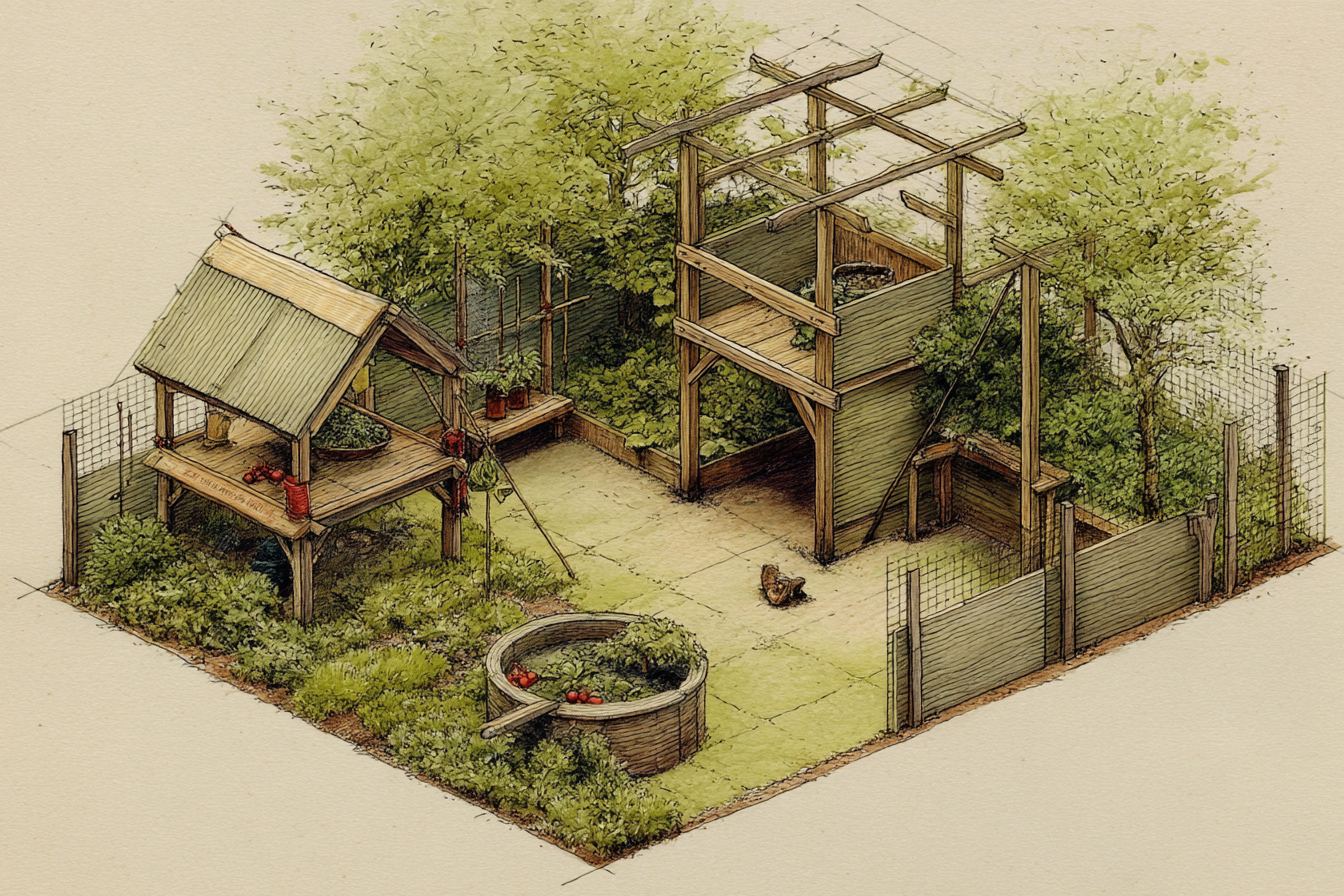

The first and perhaps most important principle is working with multiple vertical layers, just as natural woodlands do. A mature forest garden typically includes:

1. Canopy layer: Larger trees, often nut producers like walnuts, chestnuts, or almonds

2. Lower tree layer: Smaller fruit trees like apples, plums, or pears

3. Shrub layer: Currants, berries, and other productive bushes

4. Herbaceous layer: Perennial vegetables and herbs

5. Ground cover layer: Edible plants that spread horizontally like strawberries or herbs

6. Root layer: Edibles that grow below ground such as root crops

7. Vertical layer: Climbers and vines that use other plants for support

Not every forest garden includes all seven layers—mine certainly doesn’t, as I’m working with limited space—but the principle of vertical stacking is crucial. This approach maximizes productivity per square meter by utilizing different light levels, root depths, and growth habits. While a conventional garden might produce food from just one horizontal plane, a forest garden harvests sunlight energy more efficiently at multiple heights.

I learned this lesson vividly when I helped design the community forest garden. Initially, some committee members were concerned that adding trees would reduce the space available for vegetables. What we found instead was that by thoughtfully combining upper story trees with shade-tolerant perennial vegetables underneath, we actually increased the overall yield from the same footprint. The Chinese mountain yams growing up the apple trees and the Good King Henry flourishing in dappled shade beneath them simply wouldn’t have had space in a conventional horizontal layout.

The second principle that revolutionized my growing approach is the use of perennial plants rather than annuals. In conventional gardening and farming, we rely heavily on annual plants—those that complete their lifecycle in a single year, requiring replanting each season. While these can be highly productive, they also demand significant resources: soil disturbance, consistent watering, protection from competition, and regular replanting.

Forest gardens, by contrast, rely primarily on perennials—plants that live for multiple years, often becoming more productive over time rather than less. Once established, perennials typically develop deeper root systems that access nutrients and water unavailable to annual plants. They require less intervention, build soil structure, and provide habitat continuity for beneficial organisms.

The difference became laughably obvious during last summer’s drought. While my neighbor Julian was watering his traditional vegetable plot twice daily to keep his lettuce from keeling over (poor Julian—I could see the despair on his face from my kitchen window), the perennial vegetables in our forest garden system sailed through with minimal irrigation. The established trees and shrubs with their deep roots barely noticed the dry spell, and they created a microclimate that protected the understory plants.

The shift from annuals to perennials does require adjusting expectations about what food looks like. Instead of familiar annual vegetables, forest gardens often feature perennial alternatives: perennial kale instead of annual cabbage, Nine-Star Broccoli that produces for years, perennial leeks rather than annual onions. Some of these crops are unfamiliar to modern eaters but were dietary staples for our ancestors. Others are simply perennial versions of familiar foods that commercial agriculture has ignored because they don’t fit neatly into industrialized systems.

The third principle that makes forest gardening so revolutionary is the emphasis on relationships between plants rather than treating each as an isolated entity. In conventional growing, we often think about what each plant needs and then provide those requirements directly. If a plant needs nitrogen, we add fertilizer. If it’s susceptible to pests, we spray it with something or surround it with protective barriers.

Forest gardening takes a different approach, using plant communities and guilds where the needs of each species are met by other components of the system. Nitrogen-fixing plants like sea buckthorn or alders enrich soil for neighboring trees. Deep-rooted dynamic accumulators like comfrey bring minerals from deep soil layers and make them available through their leaf matter. Aromatic plants confuse pests searching for host plants by scent. Flowering species support pollinators and predatory insects that keep pest populations in check.

I’ve seen this principle transform problem areas in ways that still seem slightly magical to me. A patch in our community garden that consistently succumbed to aphid infestations was redesigned as a forest garden guild—a mountain ash tree underplanted with comfrey, wild garlic, and lupins, with climbing nasturtiums and a mix of flowering perennials. The following year, the aphids still appeared, but so did their predators—ladybirds, hoverflies, and parasitic wasps that we’d created habitat for. The system handled the problem without human intervention.

The fourth principle, which particularly resonates with my lazy gardener tendencies, is designing for self-maintenance. Forest gardens are deliberately structured to require decreasing rather than constant or increasing levels of human intervention over time. This is achieved through strategies like:

– Using ground cover plants to suppress unwanted competition rather than constant weeding

– Incorporating nutrient-accumulating plants that naturally fertilize the system

– Selecting disease-resistant varieties adapted to local conditions

– Establishing guilds of plants that support each other’s health and productivity

– Working with rather than against natural succession

This doesn’t mean forest gardens are maintenance-free—that’s a common misconception. They require significant work during the establishment phase and ongoing management, just as natural forests need disturbance to maintain diversity. But the nature of the work shifts from constant battling against nature to occasional steering of natural processes.

I experienced this shift firsthand with the small forest garden element I snuck into my previous rental property’s garden (with permission, I should clarify). The first year was labor-intensive: sheet mulching to clear grass, planting, watering to establish perennials, and protecting young plants. By year three, my involvement had dwindled to occasional pruning, some harvesting, and adding woody mulch once a year. The system largely took care of itself, with ground covers suppressing unwanted plants and the established root systems requiring minimal watering.

The fifth principle, and perhaps the most profound shift for many gardeners, is embracing abundance and diversity rather than control and tidiness. Forest gardens aren’t meant to look like traditional gardens with neat rows and distinct plantings. They’re intentionally diverse, sometimes appearing unstructured to the untrained eye, with plants mingling, self-seeding, and occasionally shifting dominance as conditions change.

This diversity serves multiple functions beyond aesthetics. It creates resilience—if one crop fails due to weather or pests, others will thrive under those same conditions. It supports complex food webs that keep any single pest from dominating. It provides sequential harvests throughout the year rather than gluts followed by scarcity. And perhaps most importantly for home-scale growers, it transforms the garden from a production space into an immersive, multisensory environment that nourishes more than just the body.

I’ve seen this principle convert even the most dedicated traditional gardeners. Mrs. Patterson from our street was initially horrified by the “messiness” of our community forest garden area. Three years later, she requested we help her convert a corner of her immaculate garden into a mini forest garden system. “It just feels so alive,” she explained, somewhat sheepishly. “And I’m tired of deadheading roses.”

Implementing these principles doesn’t require acres of land or rural isolation. I’ve seen effective forest garden systems in spaces as small as 10 square meters, on sloping sites considered “unusable” for conventional gardening, in public parks, school grounds, and even on rooftops. The approach scales remarkably well and can be adapted to almost any context where plants can grow.

For absolute beginners, I recommend starting with a single forest garden “guild”—a small polyculture centered around one tree or shrub with complementary plants beneath. This might be as simple as a dwarf apple tree underplanted with comfrey, strawberries as ground cover, garlic chives to deter pests, and perhaps a grape vine using the tree for support. This mini-ecosystem demonstrates the principles at a manageable scale and can be expanded over time.

The most common mistake I see (and have made myself, repeatedly) is trying to include too many species too quickly. Forest gardening enthusiasts tend to get carried away with the amazing diversity of unusual edibles and end up with a jumbled collection of plants without clear design logic. I still have nightmares about the “experimental guild” I created in our community garden that included 27 different species in a 2-meter circle. It was a taxonomic success but an organizational disaster that took three years to sort out.

A more successful approach is to start with the structure—deciding on canopy and understory trees first, then adding lower layers progressively as the system develops. This mimics natural succession and allows each plant to establish properly before facing competition. It also gives you time to observe how the light patterns and microclimate develop as upper layers mature, informing better choices for what goes underneath.

Seven years after that transformative visit to Martin Crawford’s garden, I’m now helping design forest garden systems for other community projects and private clients—still learning through every success and failure. My own garden space remains limited (the joys of urban living), but I’ve managed to incorporate key elements: a small apple tree underplanted with perennial alliums and herbs, currant bushes sharing space with comfrey and strawberries, vertical growing space maximized with vines and climbers.

What continues to astonish me is how these systems evolve over time. The forest garden elements I planted three years ago already look nothing like they did at the start—plants have shifted, some have thrived beyond expectation while others have struggled, and new relationships have emerged that I never planned. Yet the overall productivity and resilience increase rather than decrease with each passing season.

Perhaps the most profound insight from forest gardening isn’t about techniques or plant selections but about our relationship with the natural world. Conventional growing often positions us as controllers, constantly fighting against natural processes to maintain artificial systems. Forest gardening repositions us as participants within the ecosystem—stewards who guide rather than dictate, who work with ecological principles rather than against them.

Last weekend, I took my mother to see the community forest garden she’d heard me ramble about for years. As we stood amid the dappled light beneath the now-productive apple trees, watching bees move between flowers while picking unexpected alpine strawberries from between stepping stones, she asked a question that perfectly captured the paradigm shift: “But how do you know what’s supposed to be here and what isn’t?”

The answer, which took me years to understand myself, is that forest gardening fundamentally changes that question. In these living systems, we move beyond the binary of “desirable” and “undesirable” plants toward understanding functions, relationships, and balance. Sometimes a “weed” is providing exactly the function the system needs at that moment—mining minerals, covering bare soil, supporting insects. Our role shifts from enforcer to observer, understanding when to intervene and when to let the system’s intelligence guide the way.

That shift—from controlling to collaborating with natural systems—may ultimately be forest gardening’s most revolutionary contribution, not just to how we grow food but to how we might reimagine our entire relationship with the living world. And on days when climate news feels overwhelming, I find profound hope in these small, abundant ecosystems that demonstrate what regenerative human participation in nature can look like. That, and they produce a cracking amount of berries with remarkably little effort once established—which, let’s be honest, is a pretty compelling argument all on its own.