The first time I held a piece of mycelium packaging, I was thoroughly convinced it was a practical joke. My friend Sasha from university days—now running her family’s organic farm in Somerset—had sent me a small ceramic bowl carefully nestled in what looked like dirty styrofoam. The note accompanying it read: “The bowl is a birthday gift. The packaging is the future.”

I was about to bin the “styrofoam” when something about its texture made me pause. It was slightly rough to the touch, not quite with the squeak and shine of regular polystyrene. And it smelled… earthy? I reread Sasha’s note, then frantically messaged her: “Is this packaging what I think it is??”

Her reply came with a laughing emoji: “If you think it’s mushroom roots, yes. You can break it up and add it to your garden. It’s essentially compressed agricultural waste held together by fungal mycelium. Welcome to the future, sustainability girl.”

I stood in my kitchen, utterly fascinated. The material in my hands—something that had perfectly protected a ceramic bowl through the postal service—was completely compostable. More than that, it would actually benefit my soil. I immediately took it out to my small garden, crumbled it around my struggling tomato plants, and watered it in. Within weeks, those previously pathetic tomatoes were thriving. That’s when my obsession with mycelium materials began.

For those who haven’t yet encountered these remarkable materials, a quick mycology primer: Mycelium is essentially the root structure of fungi—the vast underground network from which mushrooms emerge as just the reproductive “fruit.” These intricate webs of thread-like cells called hyphae can spread for miles, forming the largest organisms on earth. They’re nature’s great decomposers and connectors, breaking down organic matter and facilitating nutrient exchange between plants. They’re also, it turns out, spectacular manufacturing partners if you know how to work with them.

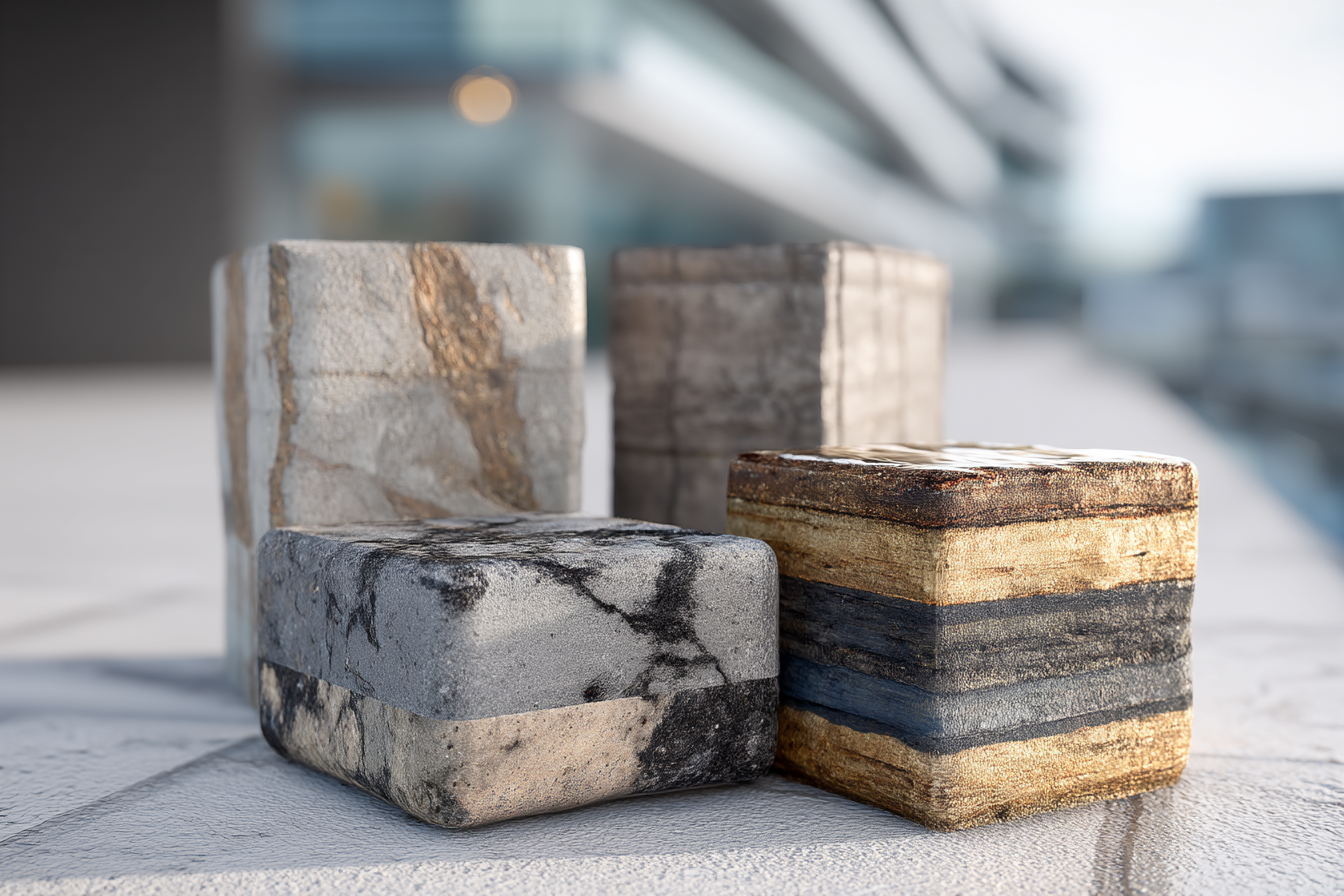

The basic process for creating mycelium materials seems almost absurdly simple: take agricultural waste (things like corn husks, hemp stalks, or wood chips), add mycelium spores, provide the right growing conditions, and watch as the fungal network binds it all together into a solid mass that can be molded into virtually any shape. Once the mycelium has fully colonized the material, you heat-treat it to stop growth, and voilà—you have a completely natural, biodegradable material that can replace everything from packaging to building materials.

My first proper research into mycelium materials beyond my garden experiment led me to a small startup in South London. Their workshop—housed in what was once an abandoned bakery—smelled like a curious mix of fresh mushrooms and sawdust. Grow rooms with carefully controlled temperature and humidity housed trays of material in various stages of fungal colonization. The founder, Marcus, walked me through their process while handling samples of their packaging with the reverence some people reserve for expensive wine.

“We’re not creating materials so much as growing them,” he explained, handing me what looked like a perfectly formed corner cushion for packaging electronics. “The mycelium does the hard work. We just create the right conditions and shape the result.”

What struck me most was how little the production process resembled conventional manufacturing. No roaring machinery, no noxious chemical smells, no extreme temperatures. Just racks of fungi quietly doing what they’ve done for over a billion years—breaking down plant matter and creating new structures. The energy requirements were minimal—mainly for maintaining temperature and humidity. The “waste” was minimal too—just organic matter that could be fed back into the next batch.

The contrast with how we currently produce packaging couldn’t be starker. Conventional plastic foam packaging involves petroleum extraction, energy-intensive processing, and the creation of materials that will persist in our environment for hundreds of years, breaking down into microplastics that are now found everywhere from Arctic ice to human bloodstreams. Mycelium packaging requires only plant waste, fungal spores, and minimal energy, creating a product that returns safely to the earth in weeks.

Since that initial workshop visit, I’ve tracked down and tested dozens of mycelium-based products. My flat has become something of a fungal materials testing ground, much to the bemusement of friends who find me enthusiastically examining molded fungi packaging like it’s a precious artifact. “You’ve reached a new level of eco-nerdom,” my housemate observed recently as I photographed the gradual decomposition of a mycelium planter in our garden. She’s not wrong.

The applications extend far beyond just packaging, though that remains the most commercially developed sector. I’ve sat on mycelium-based furniture that was both surprisingly comfortable and structurally sound. I’ve handled building insulation panels made from mycelium that outperform conventional insulation in both thermal and acoustic properties while improving indoor air quality. I’ve even worn a hat partly made from mycelium leather—though I admit the aesthetics need some refinement unless “fungal chic” becomes the next fashion trend.

One particularly fascinating area is mycelium’s potential in larger-scale construction materials. Researchers at several universities are developing mycelium-bound blocks that could replace concrete in certain applications, with dramatically lower carbon footprints. Unlike concrete, which accounts for about 8% of global carbon emissions, mycelium materials actively sequester carbon during production. And while they’re not yet suitable for all structural applications, they excel in non-load-bearing situations.

I visited a prototype tiny house in rural Wales with interior walls constructed from mycelium panels. The builder, Christine, had become interested in fungal materials after developing chemical sensitivities to conventional building products. “These walls aren’t just environmentally friendly,” she explained, running her hand along the slightly textured surface. “They actively clean the air and regulate humidity. It’s like the house is alive in a subtle way, working with you rather than just existing as a passive structure.”

That concept of “alive” versus “inert” materials represents perhaps the most profound shift in perspective that fungi-based products offer. Conventional materials manufacturing is essentially a process of killing—taking living things (trees, plants) or long-dead ones (fossil fuels) and processing them until they’re completely inert. Mycelium materials work with living processes, harnessing natural growth rather than fighting against it.

The regenerative potential is enormous. Traditional plastic production depletes finite resources and generates pollution at every stage. Mycelium products use waste materials as feedstock, require minimal energy, and return safely to natural cycles at end of life. Some companies are even incorporating seeds into their packaging so that when composted, they don’t just degrade harmlessly but actively grow new plants.

Of course, fungal materials aren’t without limitations. Current production methods struggle with consistency at scale—a reflection of working with living organisms rather than standardized industrial processes. Water resistance remains a challenge for some applications, though advances in natural coatings and processing techniques are addressing this. And while production is expanding, capacity is nowhere near what would be needed to replace conventional plastics across all applications.

There’s also the question of economic viability. Most mycelium products currently cost more than their conventional counterparts, though the gap is narrowing as production scales up and processes become more efficient. A more comprehensive accounting that includes disposal costs and environmental impacts would already make mycelium materials the economical choice in many cases, but our economic systems rarely incorporate those factors adequately.

To better understand the commercial landscape, I spoke with investors focused on sustainable materials. Zane, a partner at a green venture capital firm, explained the shifting dynamics: “Five years ago, mycelium companies were curiosities—interesting science projects with uncertain commercial potential. Now they’re securing major corporate partnerships and scaling production for mainstream applications. The tipping point is approaching where performance and price will make them competitive even without considering the environmental benefits.”

Indeed, major brands are increasingly incorporating mycelium materials into their packaging and products. Furniture companies are launching mycelium-based components. Fashion brands are exploring mycelium leather as an alternative to both animal leather and plastic-based vegan options. Building material suppliers are adding mycelium insulation to their catalogs. What was once fringe is steadily becoming mainstream.

For consumers interested in supporting this fungal revolution, options are expanding. Companies like Ecovative and Mushroom Packaging offer mycelium alternatives for conventional foam packaging. Brands like Stella McCartney and Adidas have incorporated mycelium leather into product lines. Building supply companies are beginning to stock mycelium insulation. Even smaller, craft-focused products like planters, lampshades, and decorative objects made from mycelium materials are increasingly available through sustainable product retailers and platforms like Etsy.

You can even grow your own mycelium materials at home, though I speak from chaotic personal experience when I say this approach has a significant learning curve. My first attempt at creating a mycelium planter in my kitchen resulted in what my mother diplomatically called “an interesting science experiment” but what was objectively a moldy disaster that attracted fruit flies and prompted an emergency deep clean of my entire cooking area. Commercial growing kits offer a more controlled entry point for the curious but not necessarily lab-equipped home experimenter.

The DIY disaster notwithstanding, I remain utterly convinced that mycelium materials represent one of our most promising paths away from petroleum-based plastics and other environmentally problematic materials. The elegance of the solution lies in its fundamental alignment with natural processes—harnessing an existing biological system that has evolved over billions of years rather than fighting against those systems with brute-force chemistry and physics.

In my favorite demonstration of the circular potential, I recently received a package containing houseplant supplies, cushioned with mycelium packaging. I broke up the packaging and worked it into the soil of the very plants whose nutrients it was now supporting. The cyclical poetry of it—packaging becoming plant food becoming plants that might one day become packaging material again—offered a glimpse of what truly circular material systems could look like.

The most profound shift may be in how we think about our relationship with materials. The conventional industrial approach views materials as things to be conquered, forced into submission through chemical processes and mechanical stress. Mycelium materials invite us into collaboration instead—creating conditions for natural growth processes that result in viable alternatives to synthetic products. It’s less about dominating materials and more about partnering with them.

This perspective extends to their end of life as well. While we’ve designed conventional plastics to resist natural breakdown at all costs (and are now facing the consequences), mycelium materials are designed to return gracefully to natural systems when their usefulness ends. The built-in humility of this approach—acknowledging that our materials should eventually yield back to natural cycles rather than persist indefinitely—feels like an important philosophical correction to industrial hubris.

Last month, I visited a commercial mycelium packaging facility that had scaled significantly since my first introduction to these materials. Row upon row of growing chambers housed packaging at various stages of development, with automated systems maintaining optimal conditions. The production manager, Priya, had previously worked in conventional plastics manufacturing.

“The first month here was a total mindset shift,” she told me as we watched robotic arms carefully transfer finished pieces to the drying area. “In plastics, it was all about forcing materials to behave through heat, pressure, and chemistry. Here, we succeed by understanding and supporting a natural process. We’re growing packaging, not making it. The product is alive until the very final stage.”

As we left the facility, she handed me a sample of their newest material—a mycelium foam that felt remarkably like conventional plastic foam but would compost in my garden within six weeks. I couldn’t help but compare it to that first piece of mycelium packaging I’d received years earlier with my ceramic bowl. The technology had advanced remarkably—this version was more uniform, more resilient, more refined in every way.

But the fundamental magic remained unchanged: in my hands was a piece of packaging grown rather than manufactured, born from waste rather than extracted from finite resources, destined to return to the earth rather than persist for centuries. As I added it to my garden compost, I thought about how many times I’d written about “revolutionary” materials over the years, most of which had failed to live up to their early promise. But with every mycelium product I test and every development I track in this field, my conviction grows: the fungi are coming for our plastics, and that’s something to celebrate.